Well it looks like it’s time for an encore folks. After last week’s ranty blog, I am betting that everyone is up for something more. What is he going to do next? Who’s the target? Horgan, right? It’s gotta be Horgan! (For the benefit of non-Canadian readers or those who (smartly) avoid politics, Horgan is the current premier of BC). No, it’s not Horgan, even though he is a tempting target. And it’s not anyone in the US because as I described last week I am not able to make any comments on American politics because of the shutdown (even though it’s over).

Maybe you are hoping for a little NDP or UCP bashing? Nah. Look, we all know that the election to end all elections is coming. So soon that it has started already, even though there is no date, and the major parties still haven’t bothered to fill their slates of candidates. But I am determined to avoid the trap. My pre-election call will come the Friday before the election that hasn’t been called and the appropriate celebration of my genius insights or drowning of sorrows on blown calls will follow the Friday after.

No, I will make no mention of either Jason Kenney or Rachel Notley until the appropriate time unless they either a) do something really dumb; or b) do something incredibly clever; or c) buy some paid advertising on my blog using some of the record $10 million they have collectively raised for an as yet announced election that has a spending limit of $2 million per party.

Anyway, that’s where I’m at. Trump/Pelosi aside, politics is boring for me this week. But you know what’s not boring? Energy. Capex. Earning’s reports. Venezuela. Mexico.

And I’m paying attention to all of this this week because there seems to be an accepted perception that Canada is some mega-risky place to invest. But is it?

In all reality, notwithstanding its obvious challenges, Canada is clearly not the most risky place to invest globally and in fact, given some current events and some objective analysis may indeed prove to be not so bad an idea after all

I know, it’s funny to hear me say that, especially after last week’s rant, but realize I am not saying that Canada is the “best” place to invest – we still have all the same challenges I outlined. And I was fully prepared to wait until the second half of 2019 to declare Canada back, but there I was, reading some reports, following the news and looking at some graphs and I suddenly realized that while we as Canadians have some serious issues in the energy sector (that we continue to avoid in uniquely Canadian ways) there are a lot of things at play in the rest of the world. No one is absolved from the flashing red warning light. Put another way, there are some pretty substantive issues in the energy sector that put Canada in a different light.

Skeptical? I don’t blame you, but let’s see how I got there. It all started with a Twitter exchange where one individual was discussing market penetration of electric vehicles and I pointed out the level of oil consumption (100 million barrels per day FYI) that was projected to grow through 2040 before beginning its gradual decline and then I threw out, with pretty much no corroboration or thought the following statement:

“In 10 years there will be three major suppliers of oil: Saudi Arabia, Venezuela and Canada.”

Out there right? No US (deliberate) and no Russia (accident – they should have been included). Why did I say that? I think the main reason is that collectively, these four countries represent 50% of proved and discovered global oil reserves and it’s been quite a while since any country stepped up to alter that reality, with the exception of US tight oil, which has a much smaller reserve base (arguably*) and, in my view, is a different type of contributor to the energy mix.

*Yes, I am aware of the articles saying the US has a trillion barrels of oil, but come on – that’s oil that is not yet discovered (!) or oil that is assumed to be there that can’t be recovered with current technology at current prices. Fine, on that basis Canada has 2 trillion barrels – happy now?

So how do you alter that reserve balance? You make discoveries. You invest and you spend money. Lots of money. Because not only do you need reserves to meet growing demand, you need new reserves to offset decline rates. Which brings me to one of the charts I saw this week.

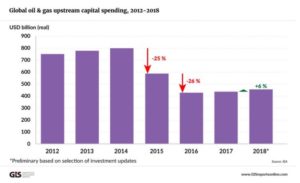

Global Capex. The following chart came across my feed this week. It shows global capex on oil for the last number of years (2012 through 2018).

First off – that’s a lot of money spent every year on upstream oil and gas (exploration and production). It’s awesome. What isn’t awesome though is the trend. What that shows is spending plunging over a waterfall, getting swept downriver by a raging torrent and has finally dragging itself soaking wet to the bank.

Global capex has fallen to levels about half of what they were in 2014. And 2018, while a year of recovery, barely moved the needle. Keep in mind as well that in 2014, that level of spending supported 91 million barrels per day of consumption.

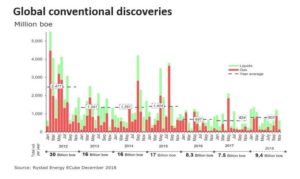

Why is this capex important? Because capex leads to discoveries and discoveries lead to reserve replacement. And if we look at a chart of reserve replacement through the same period, we can see that we haven’t been doing a bang up job at that for the last several years. I realize this is pretty boring stuff, but at a high level, when you have a declining resource, a good way to stay in the game is to try and spend enough money to find reserves to at least replace a majority of those that you have used, especially when consumption continues to increase. In 2018 the global reserve replacement was about 20%. If the globe was a publicly traded oil and gas company with that ratio, you would short it.

So we are actually using our reserves faster than we are replacing them, setting the stage for an eventual draw down in global reserves, at which point who becomes the most important? That’s right, the guys with the biggest reserves. Like I don’t know, Canada.

Okay, enough about reserves. Who cares right? We have more than enough existing reserves globally and places like the Permian are still posting record numbers and projected to grow into perpetuity. Like in an article I saw that said that within 6 years the US could be producing more than Russia and Saudi Arabia combined. Well they did double from 2008 to now, so that seems reasonable, doesn’t it? I’m kidding by the way, it’s completely unreasonable. And even if it happened, it would probably only match expected global growth in demand anyway, for a tight oil product that has limited demand upside.

Aside from that absurd forecast, barring a major price shock, most reasoned analysts expect tight oil production in the US to grow at a slower pace for the next several years, plateau and eventually decline.

Light tight oil production such as in the Permian depends on a high volume of drilling and completions to bring on a high number of wells that typically produce between 700 and 1000 barrels of oil per day in initial production. But these wells have high initial decline rates (call it 65%) so you need to drill more and more wells to keep even, let alone get ahead. This works brilliantly when finding costs are low, you have massive tracts of land containing strong reserves and nice sweet spots, your gas/oil ratio is low, capital is unlimited and you are building from a low base level of production. But what happens when any one of those variables changes? I’ll tell you what, the treadmill speeds up and it becomes harder to keep up let alone get ahead. Costs rise, production growth stalls or falls. There is a lot of evidence that this is starting to happen.

Don’t believe me? Well let’s cherry pick from a recent report. The following except is from a quarterly earnings call with Schlumberger, one of the largest and smartest energy services firms in the world.

“Conversely for the North America land E&P operators, higher cost of capital, lower borrowing capacity and investors looking for capital discipline and increased return of capital, suggests that future E&P investments will likely be at levels much closer to what can be covered by free cash flow. Assuming the trend of increased capital discipline continues in 2019 and WTI oil prices steadily recover to average the same realized level as 2018, we expect E&P investments in U.S. land to be flat to slightly down compared to 2018, with a relatively slow start to the year.

In this scenario it is likely that the E&P operators would gradually lower drilling activity and instead focus investments on drawing down the large inventory or drilled uncompleted wells. This approach would still drive production growth from U.S. land in 2019, but likely at a substantially lower rate than the 1.9 million barrels per day seen in 2018 and potentially with a further reduction in the growth rate in 2020.

It is also worth noting that with the continued growth in U.S. shale production, an increasing percentage of the new wells drilled are being consumed to offset the steep decline from the existing production base. The third party analysis shows that in 2018, this number was 54% of total CapEx and is expected to increase to 75% in 2021, clearly demonstrating the unavoidable treadmill effect of shale oil production.

Add to this, the emerging challenges of production per well as infield drilling creates interference between parent and child wells, as drilling steadily steps out from the core Tier 1 acreage and as the growth in lateral length and proppant per stage is starting to plateau, we could be facing a more moderate growth in U.S. shale production in the coming years than what the most optimistic views have been suggesting.”

What does this mean? Well first off, Schlumberger is not the EIA – they report what their clients are saying and their business tells them – it’s not a statistical exercise. Costs are rising and productivity is falling. Drilling is moving out of the core areas and new production is harder to bring on line. They quote an astonishing figure of 54% of capex being spent to maintain production in 2018, rising to 75% by 2021.

They see lower drilling activity, but higher drawdowns in the inventory of DUC’s to meet expected production growth. And with the sweet spots drilled out and production per well declining in the current price environment this suggests that the eventual plateau in light tight oil is maybe sooner and at lower production level than many are forecasting.

On the other hand, you have places like Venezuela, Canada and Saudi Arabia, and, OK, Russia where the reserve profile is different than in the US and the production profile fundamentally different. In Russia and Saudi Arabia, the pools are large, deep and conventional with a less short cycle approach to development and decline rates in a more sane 5% to 10% range with lower exploration and breakeven costs.

Leaving Venezuela for a moment, we have Canada and our 200 billion’ish reserves. Canada’s oil reserves are for the most part in the oilsands. We have conventional off shore reserves in the East and conventional and unconventional reserves across the West but the bulk of our massive oil wealth is trapped in sand. Unlike offshore and to a certain extent the LTO market, there are no finding costs associated with it. It’s mapped. We know where it is. Our issue is the cost to extract it which we are continually managing down. And we’ve barely scratched the surface, if you will excuse the mining pun.

Compare Canada to light tight oil. Canada isn’t short-cycle. The reserves are there. The decline rate is 3%. We produce a heavy oil for which there is significant global demand. There is no treadmill in Canada. Sure resources take years to develop, but once developed they are there. We spend $10 billion to develop a project that produces 300,000 barrels per day for 30 years while light tight oil has to drill 300 wells at close to $10 million a pop every 3 years to match our production. Which is better? Depends if you are about the long term production or the short term payoff. Both are fine, but are different risk profiles. Ultimately though, if we can figure out the transportation issues, Canada is, in its boring way, a less risky place to invest. So boring in fact that we didn’t even make the Schlumberger report.

Okay, moving on.

Venezuela

Venezuela, which has been said here repeatedly is the too often ignored horror of the past three years. An unfolding humanitarian tragedy of epic proportions that the media is finally picking up. A GDP free-fall rivalled only by the collapse of the Soviet Union (another chart I saw) with inflation running at more than 1,000,000% in 2018. Notwithstanding massive reserves, oil production has collapsed and is more likely to approach zero than the highly aggressive 5 million barrels per day in five years predicted by the government.

Now of course, things have gotten worse. There was an election on January 23rd and Nicolas Maduro, the incumbent president/dictator and successor to Hugo Chavez may have lost the presidency to his challenger Guaidó, yet refuses to give up his power despite popular and foreign pressure. Around the world, countries are lining up in support of one side or the other, generally divided between evil dictatorial rogue states and the rest of the world. It is a global diplomatic shuffle that may yet be upstaged by an internal conflict and convulsion that could rival Syria in how it realigns the world order, particularly as it regards oil. Unfortunately, for the last few years, the US has been isolating Venezuela making it turn to benign benefactors such as Russia and China for much needed currency for its declining exports. These state actors are dependent now on Maduro to realize any kind of return on their financial support which would be much more uncertain under any new reconstruction-oriented, US approved regime.

All of this goes to say that the situation in Venezuela is fluid and volatile. Maduro has the support of the army (for now), 20% of the population (well done!) and his paymasters in Moscow and Beijing. It will get worse before it gets better.

For two countries that have similar heavy oil reserves, I think it is safe to say that Canada is less risky than Venezuela.

Mexico

Wait, I forgot. There are the evil dictatorial regimes that supported Maduro. And then there’s Mexico. Which also did. Umm what? That’s right, the newly installed socialist government of AMLO has elected to support Maduro post-election, likely based on the same Bolivarian-loyalty infused fantasy shared by some progressives in Canada (Niki Ashton, MP) and the United States (Bernie Sanders) that Maduro represents some socialist utopian ideal as opposed to the economy pillaging thug and oppressor that he really is.

At any rate, welcome to the new Mexico. Nothing like the old Mexico.

I also read that the new Mexican congress is thinking they will withdraw approval of the USMCA – that again? Combine that with AMLO reversing the opening up of the Mexican energy sector (except to imports), a shortage of gasoline, some pipeline explosions and higher levels of crime and I have only one thing to say…

Canada is a way less risky place to invest than Mexico. Unless you want a beachfront condo – there’s only so much you can do form the North.

I could go on travelling around the world but you get the point.

I talk to lots of investors. And they say Canada (and Alberta) is a more risky place to invest than other places around the globe. Maybe they’re right, but I’m pretty sure they are wrong.

I think there’s a big difference between being perceived as a risky/bad place to invest and actually being one even if we put our worst foot forward to tell people otherwise. It’s time maybe to start changing the narrative.

How do we do that? Not through blogs like this (well maybe)., but through classic Canadian compromise and muddle-through’ism.

Let me acknowledge here that I am as if not more guilty than anyone because I have the conduit and I get frustrated, but I listen to the rhetoric that is happening in Canada and Alberta in the last little while and I have to shake my head. It’s like we have two absolute extremes instead of a collection of compromisers battling it out to carry the middle. Sure we have disagreements, some them big, but most, if not all, are manageable. And we usually manage. Compared to the rest of the world, Canada is a cake walk..

So when you have people running around claiming existential threats from this or that electoral outcome it’s nonsense to me. I try to be apolitical in this blog and call out the BS when I see it, no matter which party has deposited it. That’s what I think I tried to do last week – look at the issues objectively and point out the obvious. Trudeau was the target because he held the reins. I wouldn’t and haven’t shied away from anyone.

The only thing you do by taking extreme positions is empower the fringe. And more importantly, scare away investors before they have the time to actually do their homework and understand what they are dealing with.

Which is:

Canada is a country of laws. We are sleepy and boring. We think our internal politics are extreme but in contrast to the rest of the world, we’re a loaf of white bread. Dry, somewhat bland, makes a great sandwich. We aren’t wowing anyone. The stories are dull, it’s always cold, but we don’t turn on each other, we don’t wage wars, we like our rules even when we have too many and they seem counter intuitive to growing our economy. Our politicians are bland. From an energy perspective, our resources are difeined, measured and contained inside a world-class regulated contiguous fairway of abundance with access to both foreign markets and the world’s largest energy consumer mere miles away.

Even our scandals, such as they are, are BORING!

Overall this tells me something. Canada is and will always be a less risky place to invest than many places around the world. And will be even better if we can get out of our own way (had to get in there).

Oh. And let’s build our pipes. Makes us even less risky.

Prices as at January 25, 2019 (January 18, 2019)

- The price of oil off early then rose during the week on optimism of shutdown resolution and Venezuela chaos

- Storage posted an increase

- Production was flat

- The rig count in the US was up

- Withdrawals from storage were higher than anticipated for natural gas. Price fell…

- WTI Crude: $53.55 ($53.76)

- Western Canada Select: $44.00 ($42.56)

- AECO Spot *: $1.89 ($1.92)

- NYMEX Gas: $3.174 ($3.423)

- US/Canadian Dollar: $0.7574 ($0.7550)

Highlights

- As at January 18, 2019, US crude oil supplies were at 445.0 million barrels, an increase of 8.0 million barrels from the previous week and 33.4 million barrels above last year.

- The number of days oil supply in storage is 25.6 compared to 24.1 last year at this time.

- Production was flat for the week at 11.900 million barrels per day. Production last year at the same time was 9.878 million barrels per day.

- Imports rose from 7.257 million barrels to 8.191 million barrels per day compared to 8.041 million barrels per day last year.

- Exports from the US shrunk from 2.968 million barrels per day to 2.035 million barrels per day last week compared to 1.411 million barrels per day a year ago

- Canadian exports to the US were 4.063 million barrels a day, up from 3.571

- Refinery inputs fell during the during the week to 17.049 million barrels per day

- As at January 18, 2019, US natural gas in storage was 2.370 billion cubic feet (Bcf), which is about 11% lower than the 5-year average and about 1% less than last year’s level, following an implied net withdrawal of 163 Bcf during the report week

- Overall U.S. natural gas consumption rose 4% during the report week

- Production for the week was down 1%. Imports from Canada decreased 6% from the week before. Exports to Mexico increased 1%

- LNG exports totaled 21.6 Bcf

- As of January 25, 2019, the Canadian rig count was 232 (AB – 161; BC – 16; SK – 49; MB – 4; Other – 2. Rig count for the same period last year was 337.

- US Onshore Oil rig count at January 25, 2019 is at 862, up 10 from the week prior.

- Peak rig count was October 10, 2014 at 1,609

- Natural gas rigs drilling in the United States were down 1 to 197.

- Peak rig count before the downturn was November 11, 2014 at 356 (note the actual peak gas rig count was 1,606 on August 29, 2008)

- Offshore rig count up 1 to 20

- Offshore peak rig count at January 1, 2015 was 55

US split of Oil vs Gas rigs is 80%/20%, in Canada the split is 56%/44%

Trump Watch will return when the shutdown is really over.